Monumental Thoughts – Part 2

The Library of Congress and the National African American History Museum represent the complicated history, culture, and challenges of our nation. The Library of Congress is the world’s largest library with more than 173 million items including books, recordings, photographs, maps, sheet music, and manuscripts. The majestic building is filled with statues, murals, and quotations. Established in 1800, it was described as a library of “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” The initial modest collection burned in the War of 1812.

The Library of Congress and the National African American History Museum represent the complicated history, culture, and challenges of our nation. The Library of Congress is the world’s largest library with more than 173 million items including books, recordings, photographs, maps, sheet music, and manuscripts. The majestic building is filled with statues, murals, and quotations. Established in 1800, it was described as a library of “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” The initial modest collection burned in the War of 1812.

Thomas Jefferson then donated his personal library to restart the collection. As with the Capitol art, the Library of Congress’s main reading room mural presents figures representing “countries, cultures, and eras that contributed to the development of Western civilization as understood in 1897.” [from LOC visitor guide]. Bronze statues portray “men who devoted their lives to the subject represented by the statue above them.” These are Moses and St. Paul (religion), Robert Fulton and Columbus (Commerce), Edward Gibbon and Herodotus (history), Beethoven and Michelangelo (art), Francis Bacon and Plato (philosophy), Homer and Shakespeare (poetry), James Kent and Solon (law) and Joseph Henry and Isaac Newton (science). These statues look down on the 236 desks used by researchers accessing the library’s collections.

Fourteen avenues to the west, the National African American History Museum (NAAHM) rises on the mall, design inspired by an African crown. It took over 100 years from when the idea for such a museum was first presented until the official opening. I have great appreciation for those who persisted and made it happen. It is a must-see for anyone visiting Washington, and visiting Washington is a must-do for everyone.

Fourteen avenues to the west, the National African American History Museum (NAAHM) rises on the mall, design inspired by an African crown. It took over 100 years from when the idea for such a museum was first presented until the official opening. I have great appreciation for those who persisted and made it happen. It is a must-see for anyone visiting Washington, and visiting Washington is a must-do for everyone.  While we admire Thomas Jefferson for so much in our history, and named the main Library of Congress building after him, in addition to his stately memorial on the Tidal Basin, the NAAHM shows Jefferson in front of a pile of bricks, each with the name of one of the enslaved people at Monticello. The museum has four floors dedicated to the history of slavery, and it is brutal and blunt. I was pleased to see a delegation of public safety leaders (police and fire chiefs and senior staff) from a nearby Maryland county touring the museum with a Black tour guide. This is important history for us all to understand.

While we admire Thomas Jefferson for so much in our history, and named the main Library of Congress building after him, in addition to his stately memorial on the Tidal Basin, the NAAHM shows Jefferson in front of a pile of bricks, each with the name of one of the enslaved people at Monticello. The museum has four floors dedicated to the history of slavery, and it is brutal and blunt. I was pleased to see a delegation of public safety leaders (police and fire chiefs and senior staff) from a nearby Maryland county touring the museum with a Black tour guide. This is important history for us all to understand.

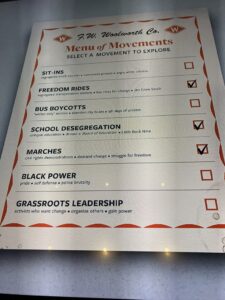

The history section continues to the present, documenting scholars, soldiers, educators, politicians, and other Black leaders, as well as the struggles they endured. There is a lunch counter where visitors can consider choices made by civil rights activists.

The history section continues to the present, documenting scholars, soldiers, educators, politicians, and other Black leaders, as well as the struggles they endured. There is a lunch counter where visitors can consider choices made by civil rights activists.  When you exit the history section, the museum offers a “contemplation courtyard” which I felt much need for as I was overwhelmed by emotion.

When you exit the history section, the museum offers a “contemplation courtyard” which I felt much need for as I was overwhelmed by emotion.

The museum was well attended. There were groups that comprise the annual “eight grade migration,” school groups on their spring vacation. I bristled at seeing adolescents sporting “Trump 2024” hats amid their fellow students, but perhaps they read some of the exhibit materials and learned a bit. One can hope.

There were plenty of Black families sharing their heritage with their children. I was proud to see two handsome Black women in full US Army dress blue uniforms, both sporting many ribbons and decorations that I presume mean they have been successful in their military careers. I’m conflicted about all the corporate donor recognition plaques. It’s wonderful that this museum exists and it takes money to make that happen. So good for these corporations for donating some. Again, I fear this is a bit of window dressing, and wonder how many executives have really taken in the history in this place, and taken action to dismantle racism in their organizations and those where they have influence.

There were plenty of Black families sharing their heritage with their children. I was proud to see two handsome Black women in full US Army dress blue uniforms, both sporting many ribbons and decorations that I presume mean they have been successful in their military careers. I’m conflicted about all the corporate donor recognition plaques. It’s wonderful that this museum exists and it takes money to make that happen. So good for these corporations for donating some. Again, I fear this is a bit of window dressing, and wonder how many executives have really taken in the history in this place, and taken action to dismantle racism in their organizations and those where they have influence.

So I conclude this set of Washington blog posts still feeling a jumble of emotions. We have come a long way from our early history. We have a long way still to go. I am amazed that the political will existed to construct these great museums and monuments. Each reflects its own time in history. I recognize that progress is not necessarily a smooth path. There are setbacks and wrong turns, but I am still hopeful that the arc of the moral universe continues to bend toward justice, and that our institutions and monuments will continue to reflect the changing horizon.